Deep Sea Science:Deep Sea Reveals Insights on Human Immunity

Scientists have discovered bacteria from the deep sea with components that are unrecognizable by the human immune system and may hold important properties in the development of cancer treatments and vaccines, according to a collaborative study published in Science Immunology.

The findings, published last week, contradict the long-held belief that human cells can recognize any bacteria they come across. The study, conducted by researchers at the Rotjan Marine Ecology Lab at Boston University, the Kagan Lab at Boston Children's Hospital and the government of Kiribati, looked at the properties of bacteria from the deep sea collected on a Schmidt Ocean Institute expedition in the Southern Pacific Ocean.

Bacteria from the deep sea were found to have "immuno-silent properties" that neither harm nor benefit the body and in fact are not even detected by the immune system. Those unique properties could be used to better understand how the human immune system is programmed to attack foreign invaders like bacteria or viruses, and could have great potential in developing novel therapeutic treatments for cancer and other diseases (patents pending).

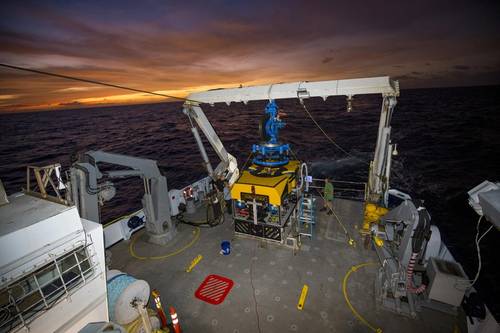

Schmidt Ocean's research vessel Falkor traveled to the Phoenix Islands Protected Area (PIPA) in 2017 with an interdisciplinary team of scientists to explore and document the region's deep sea ecosystems for the first time. PIPA is the largest and deepest of the UNESCO World Heritage sites and the first internationally recognized Marine Protected Area (MPA) to be established by a least developed nation – The Republic of Kiribati. Over 80 percent of the deep-sea microbes and bacteria collected were found to be immuno-silent to mammals.

“The diversity of chemical structures expressed by microbial life in the deep sea is totally underexplored and was completely unexpected,” said Randi Rotjan, research assistant professor at Boston University, co–chief scientist of the Phoenix Islands Protected Area, and co–lead author of the paper. “This paper provides the first detailed examples and lays the foundational groundwork, but there is so much more to be done.”

Rotjan, whose research focuses on how living corals respond to wounds from predators, says that the interdisciplinary nature of their team was also a major strength. “Studies like these help to demonstrate the value of marine protected areas and conservation. Although most of the deep sea is unknown and unseen, it is clear that it has transformative potential both for the ocean and for ourselves.

Image courtesy Schmidt Ocean Institute

Image courtesy Schmidt Ocean Institute

“The deep sea may harbor the world's largest resource of exciting biomolecules to enable new immunotherapies--much larger than Rainforests,” says Jonathan Kagan, PhD, Boston Children’s Hospital. “And importantly, we learned that our immune defenses are not universal--they work best to detect bacteria from the local habitat.”

In June, research vessel Falkor will return to PIPA under Rotjan, who will be joined by PhD student Anna Gauthier, lead author of the paper in Science Immunology, who is co-mentored by both Rotjan and Jonathan Kagan, the Marian R. Neutra, PhD Professor of Pediatrics at Harvard Medical School and the Director of Basic Research at Boston Children’s Hospital. The team will also include a Kiribati collaborator and other collaborators from Boston University and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. In addition to ecologically characterizing the deep sea coral and sponge communities, the team hopes to investigate the innate immune potential of the deep-sea corals themselves, culturing and testing the response of living corals against diverse bacteria while at sea. The results from the current study and potential outcomes from future work help to further justify the importance of marine conservation for the future of healthy ecosystems, and healthy humans.

February 2026

February 2026