Marine Telemetry: Shedding Light Below the Waves

Marine telemetry can help species conservation and management in a changing climate

An OTN Liquid Robotics Wave Glider. © Nicolas Winkler Photography

An OTN Liquid Robotics Wave Glider. © Nicolas Winkler Photography

The end of 2022 marked a potentially significant time for climate activists, scientists, and policymakers worldwide with two United Nations climate conventions—the 27th Climate Change Conference (COP27) in Egypt and the 15th Biodiversity Conference (COP15) in Canada. While neither represented the pivotal change that many hoped for—and argued was necessary—widespread dissatisfaction served as a sore reminder of the action still required from many major-polluter nations. Despite a lack of intergovernmental commitment, environmentalists globally are still working to understand the impacts of climate change on oceans and biodiversity.

In the face of a warming climate, biodiversity is declining as organisms lose habitat to anthropogenic and natural destruction; many try to migrate to more comfortable climates. Species that are unable to adapt face local extinctions and the subsequent decrease in genetic diversity places many organisms at risk of disease—including those the human population rely on for sustenance. In the oceans alone, climate change impacts sea levels, acidification, currents and temperatures. As such, it is increasingly important to better understand and manage marine biodiversity trends on a global level. And while mass oceanic data collection was once thought too difficult to rely on, scientists now have an answer: marine telemetry.

Tracking the Truth

Marine wildlife telemetry takes two common forms: acoustic and satellite. Acoustic tags are predicated on a system of transmitters, either implanted in or attached to an animal. As the organism comes within range of a previously placed receiver, their acoustic signal is recorded, and researchers can then identify which animal was tagged, as well as data like depth or temperature (if the tag is equipped with those sensors). Mark Jollymore, president at Innovasea, an aquatic solutions company that specializes in aquaculture business and wild fish tracking, identified two factors to consider with acoustic telemetry. First, acoustic tagging is limited to the number and placement of receivers in a smaller, more defined area. Second, transmitter size dictates which species are tagged and how long the technology operates for.

“Our largest transmitter, as big as one of your fingers, would be put into something like a shark, tuna or large salmon,” he explained. “The smallest transmitter would be a fraction the size of a Chiclets gum, for instance, and be put into a salmon smolt. The largest transmitter maybe operates 10 years or more, but the smaller transmitter would only last maybe four to six months.”

Satellite tags, on the other hand, are attached to the animal externally and transmit collected data upon breaching the surface—either as the animal comes up for air (if it’s a mammal), or when the tag eventually falls off and floats to the surface. While an important technique, and sometimes used in tandem with acoustic telemetry to broaden the scale of data collection, satellite tags are also significantly more expensive and likely to fall off as they can only be attached externally.

Innovasea is also working on a novel type of fish tracking—tag-less detection technology that combines “optical cameras, imaging sonar and artificial intelligence to detect, count and classify fish in real time,” according to a recent blog post. Recent testing at White Rock Dam in Nova Scotia monitored alewife migration patterns and resulted in a strong efficacy rate.

Additional Innovasea projects include tracking sharks along human-populated coastlines and beaches to provide real-time data of shark activity to lifeguards and monitoring fish activity within marine protected areas (MPAs) to determine if their placement positively impacts species.

A mobile app to track the fish detection activity as a part of Innovasea’s tagless tracking project at White Rock Dam in Nova Scotia. © Innovasea

A mobile app to track the fish detection activity as a part of Innovasea’s tagless tracking project at White Rock Dam in Nova Scotia. © Innovasea

Innovasea’s HR2 receiver. © Innovasea

Innovasea’s HR2 receiver. © Innovasea

It’s Manta Be

MPAs are an essential conservation tool for protecting migratory species, biodiverse-rich waters and vulnerable ecosystems from anthropogenic pressures like resource extraction and development. However, questions have arisen about where future protections should be put in place, and if current MPAs have had positive impacts on their species and habitats, especially in areas that are data deficient and have sparse management.

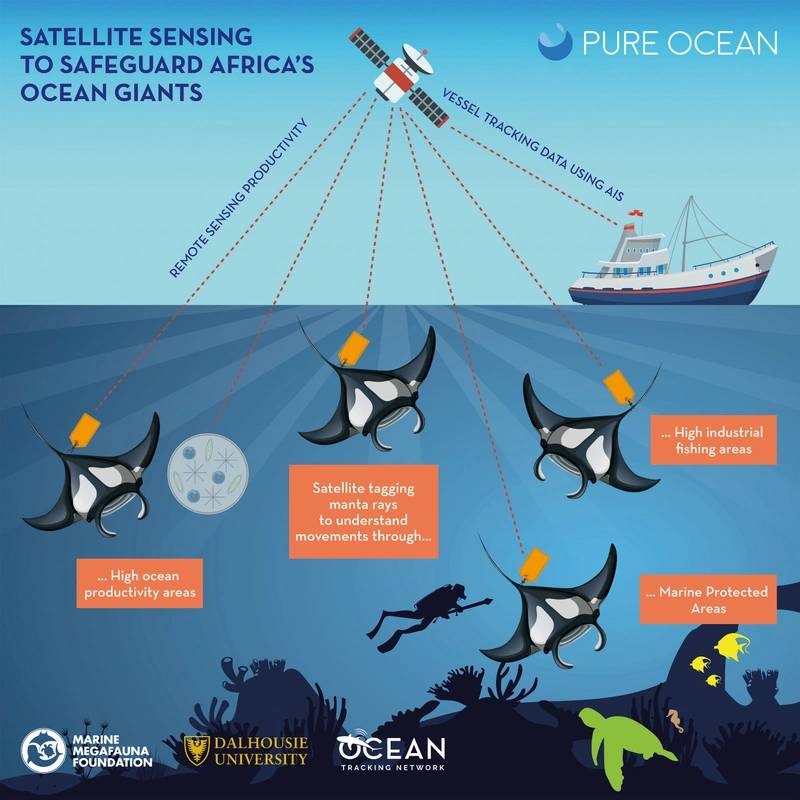

“You know, we have no idea where marine species are spending most of their time. We have no idea if marine protected areas are working. That was kind of the motivation behind it,” said Nakia Cullen, a research manager at Megafauna Foundation and PhD candidate at Dalhousie University in Halifax. Cullen lives and works in Zavora, Mozambique, an area rich with sharks and manta rays, but also data deficient and lacking the extensive management necessary. While her research started as underwater visual surveys, Cullen has been able to delve into telemetry in the past few years, inspired by other southern African marine researchers.

Cullen utilizes both acoustic and satellite telemetry to increase understanding of species movement. Satellite tags provide a wide range and more data, while acoustic tracking enables researchers to hone in on an important area to track finer scale movement during a longer period. Furthermore, each species requires a different telemetry method and archival satellite tags are particularly beneficial for manta rays, who don’t breach the surface often. Between these periods, the tags can collect and store significant amounts of data regarding the manta ray’s movements.

“I'm finding really interesting things and I think it's a great tool to highlight these critical areas,” explained Cullen. “In South Africa, for example, the mantas are hanging out in the sanctuary and they seem to be quite safeguarded there. Whereas in Mozambique, we don't have much marine protection and our mantas are declining rapidly. So, it’s important to be able to show this information to the government and be like, ‘Look, this area is really, really important.’”

Seize the Data

As the oceans change due to unprecedented anthropogenic stresses and aquatic species struggle to adapt (or fail to do so altogether), telemetry becomes an increasingly important tool to understand the unknown and how to procced with conservation and management efforts. Beyond gathering information on wildlife movement, telemetry also captures environmental conditions.

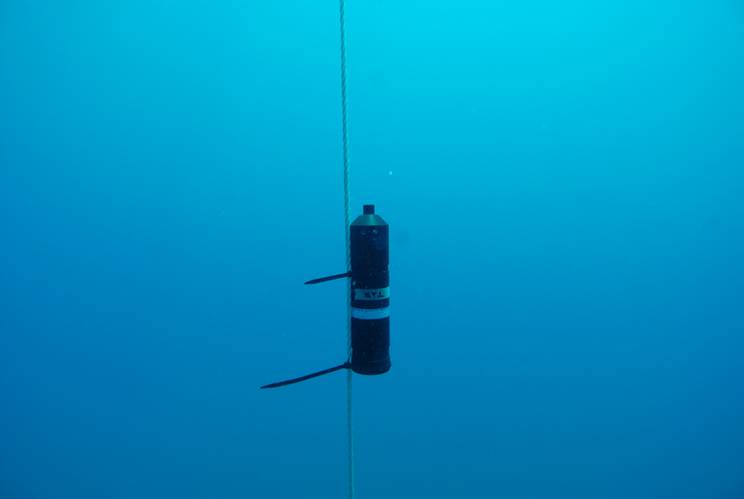

The Ocean Tracking Network (OTN), a global aquatic research, data management and partnership platform headquartered at Dalhousie University, operates a fleet of autonomous vehicles—ten Teledyne Webb Slocum gliders and four Liquid Robotics Wave Gliders. The former are electrically powered and collect physical, biological and chemical information, while the latter are solar and wave powered, gathering data on weather and sea surface conditions. Additionally, OTN maintains a loaner pool of Innovasea Vemco acoustic receiver units for use by those in academia, government, non-profits and industry.

The organization is also home to the OTN Data Centre (OTNDC), which connects a global community of researchers, trains others to use open-source data analysis tools and contributes to the development of global data standards, stated communications manager Anja Samardzic. “OTN partners with several acoustic telemetry networks around the world that work in concert to maintain inter-compatible data nodes,” she explained. “An OTN node is a replica of OTN’s acoustic telemetry database structure, which allows for direct cross-referencing between the data holdings of each regional telemetry-sharing community.” As a migration data repository, the OTNDC aids in the collection, aggregation, preservation and dissemination of aquatic telemetry—both globally and in collaboration with regional tracking networks.

One key OTN collaboration is with the Fundy Ocean Research Centre for Energy (FORCE), which is testing instream tidal turbines in the Minas Passage, through which an estimated 70 fish species travel. “As part of the Fundy Advanced Sensor Technology program,” Samardzic shared, “FORCE provides moorings that monitor current speed and turbulence, ambient noise and water quality, as well as host OTN receivers to detect tagged animals.” The implications of this work include assessing the potential impact of instream tidal power on the surrounding environment and the interactions between tidal turbines and marine life.

Nakia Cullen’s research plan for satellite telemetry in south African oceans. © Cullen

Nakia Cullen’s research plan for satellite telemetry in south African oceans. © Cullen

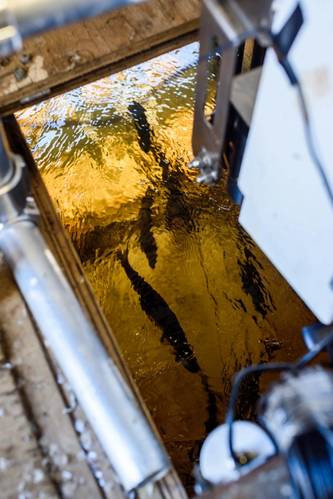

Cullen checking an acoustic receiver. © Anna Flam

Cullen checking an acoustic receiver. © Anna Flam

Cross-Ocean Collaboration

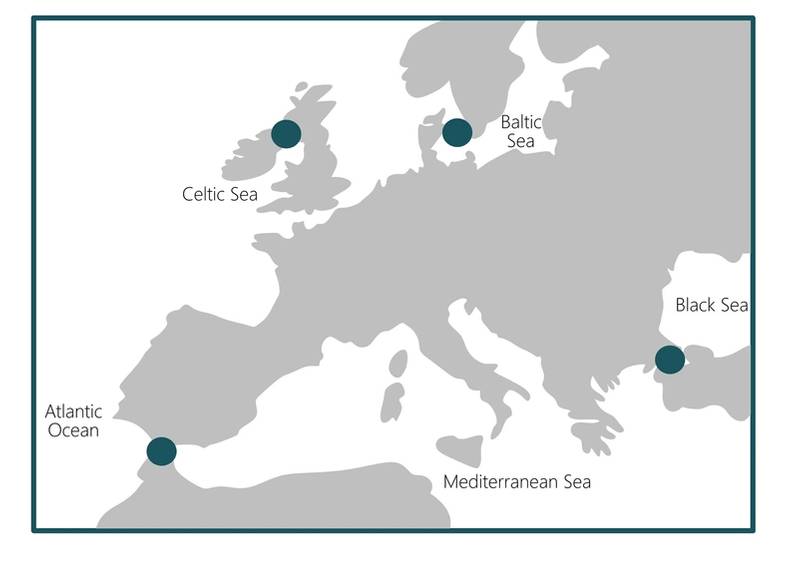

For years, scientists across Europe have been tracking fish to gain insight on behavior and movement patterns, resulting in the formation of the European Tracking Network (ETN). ETN’s newest collaboration takes the form of the Strategic Infrastructure for Improved Animal Tracking in European Seas (STRAITS) project. STRAITS aims to “instrument all four corners of Europe, covering the movements of aquatic life across some of the most important swimways on the continent,” noted Kim Birnie-Gauvin, researcher at the Technical University of Denmark and science communicator for ETN and STRAITS. The “four corners” were identified as areas between different seas (and thus, management regions) and with varied habitats.

The STRAITS infrastructure will consist largely of two components—first, acoustic receivers to detect tagged fish, operating within 63-77 kHz. Secondly, passive acoustic receivers, like C-PODs and SoundTraps will listen for cetaceans. “C-PODs monitor the presence and activity of toothed cetaceans by detecting and analysing trains of echolocation clicks,” explained Birnie-Gauvin. “With the help of an automated data analysis software, C-PODs can identify dolphins, porpoises and echolocating cetaceans (except sperm whales) from quite a distance. SoundTraps are underwater sound recorders that can listen for sounds made by cetaceans but also noise pollution, including boating activity, seismic surveys.”

“Fish and cetaceans aren’t constrained in their movements—they don’t see borders. They roam the wide ocean and tracking their movements in such a vast area comes with challenges,” said Birnie-Gauvin. “If we are to really assess both the needs and threats that these species face, we need to monitor them over much longer timescales and larger spatial scales. We can also combine movement information with environmental data and anthropogenic threats like fishing pressure, or pollution events, to understand how they respond to these factors.” In addition to combining data on different trends and factors, STRAITS works closely with other global tracking networks (OTN included) to share data, but to also identify what they call “orphan tags”—detections from outside their respective regions.

Solving the Puzzle

Aquatic animals, as Samardzic put it, support global food security, contribute billions of dollars in socioeconomic benefits and ecosystem services, and have public and cultural significance. As the climate warms and oceans change, species are forced to migrate and adapt, and their subsequent behaviors and movement patterns hold critical importance in conservation and management. “I think it’s an amazing tool, at least for migratory species,” said Cullen excitedly. “We're getting so much insight into what these animals are doing, like going to 500 meters at night to feed and then traveling 800 kilometers down the coast for god knows why. It’s like piecing a puzzle together.”

Telemetry is a solution to this challenge, and to that of large-scale data collection. “I think the future is going to be about getting more information from more spots in the oceans, rivers and lakes,” said Jollymore. “We have to figure out ways of getting data through the water and into the hands of the resource managers, the researchers, the regulators and the public.”

Birnie-Gauvin emphasized, “We’ll always have some surprises—wildlife is wild after all—but we need more permanent infrastructure if we are to get a fuller picture of the oceans. Given the state of the planet, and the rate at which it’s changing, doing so is imperative.”

The “four corners” for tracking identified as part of STRAITS. © STRAITS Project

The “four corners” for tracking identified as part of STRAITS. © STRAITS Project An acoustic tag implanted in a European seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax), Belgium. © Jérôme Bourjea

An acoustic tag implanted in a European seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax), Belgium. © Jérôme Bourjea

December 2025

December 2025