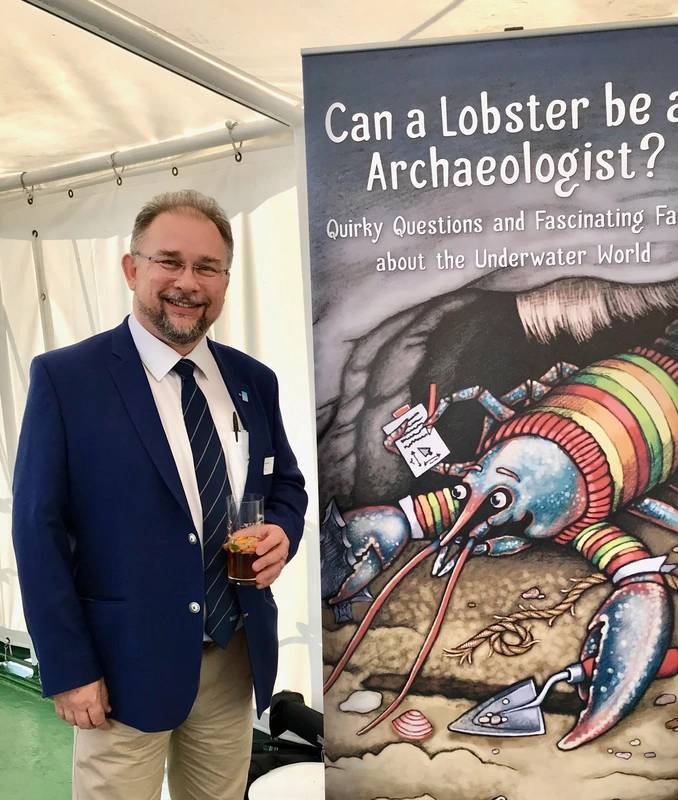

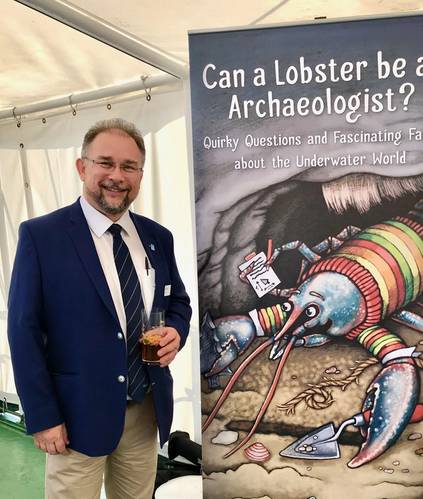

VIDEO Interview: Steve Hall, Chief Executive, Society for Underwater Technology

Last month MTR interviewed Steve Hall, Chief Executive of the Society for Underwater Technology (SUT), for his insights on the growth, pace and direction of subsea technologies. Nuclear powered and nuclear armed AUVs? It’s all on the table for Hall as he looks back on his career and tenure leading SUT, and ahead to his next chapter as the CEO of the Pembrokeshire Coastal Forum at the end of 2020.

- Steve, to start us off, can you give us a brief personal and professional background?

I suppose mine was fairly untypical background. I received a marine science degree back in the 1980s intending to join the Royal Navy. But with various defense cuts, that never happened. So, I found myself working as a surveyor in coastal surveys. I then became a customs officer, working as a specialist to oil refineries, supervising pipeline installations and tank integrity at large oil refineries. After three or four years of being a customs officer, my wife saw a recruitment advert for the “James Reynolds Center for Ocean Circulation.”

I discovered it was a project called the World Ocean Circulation Experiment which has been put together by the International Marine Science Community. So I sent in my CV, and they got in touch and said, “Customs officer with a marine science degree, there must be a way we can use you.” And the next thing I knew, I found myself working for the UK’s Natural Environment Research Council. I ended up doing spectrometer work, gas chromatography work and going off to sea, usually the Southwest Indian Ocean, skirting around the edge of Antarctica out there in the Roaring Forties and the Fearsome Fifties, learning about what it is to sort of hang onto your bunk so you don’t roll out at night. At the same time, I learned firsthand that incredible comradery you get from working with a small group of men and women in these research ships.

- Yes, those are the sorts of destinations that, today, people will spend a lot of money to visit on a small expedition cruise ship.

(That’s right) and (when you’re our there) you’re thinking, “Hey, I’m getting paid for this,” as you wake up to the penguins on the iceberg. I did that for quite a long time. I worked for the research council right through to 2017. I supervised the move to the new National Oceanography Center when that opened. I ended up doing a long stint with the Autosub, autonomous underwater vehicles program as a project manager there. Then I moved more into the climate change side of work. My last decade in public service (was spent) on the policy end of the spectrum, helping governments draft laws and policies, developing the UK’s Marine Spatial Planning system, contributing to the UN system on how we look after resources in areas outside national jurisdiction, and also the law as it pertains to marine autonomous systems.

In 2017 the opportunity to join SUT as the chief executive, so I applied for and got the job.

- Can you give to us an overview, a “by the numbers” look at SUT today?

We are an international marine learning society formed in 1966. Many of the original members of SUT were Royal Navy, mine clearance divers, military divers for the most part who in their off-duty hours were out (diving and) discovering. One of the reasons they formed a society was so that instead of just going out, having a dive and coming home, they could actually write up what they had seen.

As that group went on to do other things (many of them ended being the first generation of hard-hat divers in the North Sea), SUT quickly moved on from its original scientific diving/marine archeology/defense diving side into being a society, still very diving dominated but increasingly moving into the oil and gas sector, particularly as the North Sea expanded. So the society carried on growing through the 1970s and 80s, budding off into other countries, particularly where there’s a strong oil and gas sector.

"So here we are in the first quarter of the 21st century, and we’re still using a 1907 piece of legislation which was never intended to apply to a nuclear robot with a whopping grade thermonuclear nuclear warhead on the end of it. And I think both in the defense sector and also in things like autonomous shipping, we really need to start getting our grips not just on the technology, which is moving ahead at a fantastic pace, but make sure that our policy and legal frameworks are keeping pace with how the technology goes."

"So here we are in the first quarter of the 21st century, and we’re still using a 1907 piece of legislation which was never intended to apply to a nuclear robot with a whopping grade thermonuclear nuclear warhead on the end of it. And I think both in the defense sector and also in things like autonomous shipping, we really need to start getting our grips not just on the technology, which is moving ahead at a fantastic pace, but make sure that our policy and legal frameworks are keeping pace with how the technology goes."

- Is SUT still focused primarily on offshore oil and gas?

There are other part of the membership; you have a London branch focused on oil and gas, but also other things like marine autonomous systems and marine spatial planning. Increasingly, there are new people from other sectors, such as insurance, law, finance, coming in. And then we have branches in Newcastle that are much more interested in the offshore renewables side, (an area) which is growing rapidly in our membership. There is quite a significant defense interest as well, and the major marine universities tend to have membership too.

Like similar societies, we have a number of special interest groups. So you have groups interested in things like salvage and decommissioning, broad underwater technology, in diving and manned submersibles, even things like hyperbaric medicine. And there’s a small but very active group of media divers, the sort of people that make James Bond movies.

- The “Hollywood” end of the business sounds, pardon the pun, entertaining!

One of the most popular annual trips we do is to go down and visit Pinewood Studios near London with some of our media divers, who show our members how they work, how they stage these extraordinary scenes. There are many wonderful stories of well-known Hollywood actors and actresses who may not have ever done a day’s diving in their life who are suddenly expected to do quite a dangerous stunt. They have to keep them in the tank with the mouthpiece in until the last possible moment and hoist them out and stick in the stunt person, lest they accidentally bump off their multi-million dollar actor. An interesting bunch of people, and some real characters, some that have been with us literally from the start.

- Really, members since SUT was founded in 1966?

We still have some that joined us in the 60s, some of whom are still diving, still making discoveries. We’ve got one guy – Dr. Nick Fleming – who lost the use of his legs years ago in a road traffic accident. He’s still out there in his 80s diving, making scientific discoveries, he’s really interested in drowned landscapes, the places where humans used to live that have been lost to sea level rise over the centuries. You meet characters like that, and they’re truly inspiring human beings that make you think, “Wow, I hope I can still be as fit and active and interested as that when I get to their age.” SUT has a terrific heritage.

- When you look at the last three years you’ve spent there, what do you count as the society’s greatest achievements?

I’d say to me it’s increasing our footprint in new territories. That’s been significant. We’re growing well now in China, we have the new branch out in the Middle East, and this one that’s just starting in Canada.

For the first time, we’re sponsoring PhD students; we never did that before, and it’s been done through the generous help of the Sonardyne Foundation.

And the other thing, which is literally just starting, that I think will go a long way is that in partnership with Marine Technology Society and with the Institute of Marine Engineering, Science and Technology, we’ve now introduced the possibility for our members to pursue chartered status. So the first cohort of volunteers, the Guinea pigs, as it were, are going through at the moment.

- So when you start looking ahead, where do you see opportunities for growth in the sector.

We have already seen that there’s this huge take-up of offshore wind, which is now transitioning to being offshore floating wind. In China, I’ve seen the first examples of floating solar, and I think that’s going to end up being a huge industry as well. We’re seeing this massive take-up of autonomy both from things like the offshore survey systems, but also in the defense field. And the other industry which I think is going to be absolutely vast, and we’re just at the very beginnings of it now, is hydrogen. That is going to be massive. Whether it be blue hydrogen, the hydrogen that’s being derived from natural gas, and then you capture the carbon and put it back into the rocks, or whether it’s the green hydrogen, hydrogen that’s been electrolyzed from sea water using renewable electricity.

And I suspect that by the time we get to 2030 the offshore hydrogen industry is going to be massive. Hydrogen, I think, is going to be key to being able to decarbonize things like locomotives, ships, trucks, for example. The small private automobile is going to be fine running on batteries, but fuel cells is where it’s going to be at for large-scale, heavy duty use.

- Watch Steve Hall's Interview on MTR TV:

- The push for decarbonization is driver in many sectors?

Even if CO2 had no effect whatsoever on (the earth’s) temperature, we know it’s changing the acidity of the oceans, we’ve got to tackle that. And then you have all those associated things like sea level rise, which is going to end up killing an awful lot more people than temperature rise will. There’s some very serious issues as you start melting Antarctica and Greenland. And we’re not just talking 30, 40 centimeters of sea level rise, we’re talking meters. We’ll still need oil for all those 1,001 other things that you use oil for, we’ll still need gas, but probably not in the quantities we need them today. And I think the other big area we’ll see a lot of development in is aquaculture.

- Aquaculture?

You could say that the way we look after the ocean is like we never evolved from “hunter gatherer” mode.

In land use centuries ago, folks figured out how to plant a crop and to not bother chasing mammoths around the savannah anymore. But in the oceans, we still pretty much behave like those cavemen. We’re sending out these ships, catching all the animals, and of course there’s no big fish left anywhere. And I think one of the other big cultural and societal changes we will see over this next half century is a gradual shift from wild-caught fishing into managed aquaculture-based systems, maybe on a really large scale, ocean ranching rather than fishing.

It requires changes in the law, changes in ownership models, but we’ll see a lot of this. And there’s some fantastic work being done, particularly in the U.S., companies like BlueNalu and Finless Fish doing some fantastic work now using in-vitro technologies, cellular agriculture to be able to make fish without the thing ever having swam in an ocean, just making fish flesh.

So there are lots of changes and crossover between all of the different marine technology sectors, because the technology used on one side will be a value to somebody else as well. I don’t think we’ll see quite so much of this kind of ‘silo mentality’ in the future where folks land (and stay in) just one sector. I think we’re going to see a lot more flexibility, particularly from the kids as they come through and maybe spend some years in industry, then go across to academia, maybe then over into government, then back into industry throughout a long career.

It’s one of the valuable roles the learning societies and professional bodies play is acting as perhaps that spine that follows them through that long career. So we’re going to see a lot of changes, and that will be where publications like Marine Technology Reporter have an important role as well in maintaining and building that community as people spread out into such a wide range of other interests.

There are a lot of organizations and professional societies, there are also a lot of distractions for people today … everyone is busy. When you look at SUT, what makes it unique? What do you taut as the chief value of being a member?

I’d say the chief value of SUT is the networking, meeting people who don’t do exactly the same thing as you, but they’re operating in the same medium. People united simply by their use of underwater technology. And it might be something like filming a James Bond movie, or it could be about capturing and storing carbon dioxide, or it could be learning about how we’re going to safely and sustainably mine the sea floor in the future. And the only kind of common denominator that ends up linking all those people is they’re working in this kind of cold, corrosive, dangerous environment that’s also extremely beautiful and quite an inspiring place.

Very few people who ever go to sea who are lukewarm about it. They either love it to bits or they hate it, and never go back again. I tend to find that a lot of the people who work in marine, even if they’re doing a job which folks might think of as kind of a ‘dirty and polluting’ job, they care deeply about that marine environment. I’ve never met an oil worker who wants there to be an oil spill. They learn to value that space that they work in, and they care very much about it.

The other thing which is very noticeable is the lack of national boundaries; people think of themselves as mariners first. It’s like how back in the Cold War, the first people to be horrified when they heard about the sinking of a Russian submarine or something would be the service men working on the U.S. or the Royal Navy submarines.

I think you find that in our community full stop; we care about what our colleagues are doing, whether they’re out in the South China Sea or if they’re off the coast of Africa or in the middle of a North Sea storm ... everybody is facing those same hazards, the same beauty, the technical challenges. How do you anchor a wind farm in turbulent waters? Is it possible to extract manganese nodules or ferromanganese crusts from the deep sea bed without completely destroying the local ecosystem? We’re all aware of these challenges. And even after all of these years, there’s so little of the deep ocean floor that we’ve really explored.

I was privileged to be talking online to Don Walsh recently, who of course famously went down to the bottom of the Marianas on the Trieste in 1960. Don is an inspiring guy because he helps remind you that, until very recently, more people have walked on the moon than have ever visited the deepest parts of the ocean. There are still enormous gaps in our real knowledge about what’s happening down there in the depths. Now, we’re constantly having surprises discovering creatures we never knew about, geological processes that are new to science, and there’s still an awful lot to learn.

One of the things that excites me is that the technologies and techniques we’re learning on this world will be the things we end up applying in other worlds in the future as well. I’m sure your readers will be very familiar with some of these proposals for missions to Jupiter’s moon Europa, for example, and being able to put autonomous vehicles into these waters, getting under the ice, looking at the hydrothermal vent fields that we might find on Jupiter’s moons and discovering who knows what down there.

That’s really an exciting thing is if you’re in your 20s or 30s now, because it’s probably going to happen in your working life. If you’re doing your doctorate in engineering right now, there’s a pretty good chance that before you retire that the vehicles that you helped design may well be exploring the sea bed of other worlds.

So I think it is a challenge for society as a whole to encourage people to understand that there is one planet, one ocean, that we’re all interconnected. And that ocean that used to divide us all is actually the thing now which unites us.

So I think it is a challenge for society as a whole to encourage people to understand that there is one planet, one ocean, that we’re all interconnected. And that ocean that used to divide us all is actually the thing now which unites us.

- This is a transcendent time for the subsea industry with the convergence of drivers and technologies. When you look at the market today, what do you count as the top two or three drivers that are really moving the ball forward?

Although not all countries are taking part, the planet as a whole is moving fast towards decarbonization. And in fact, the countries that don’t do it are going to find themselves at a significant competitive disadvantage because they’ll find that their competing countries will move to a whole new level of technology, and they’re still burning oil. That policy driver, the need to decarbonize, is certainly changing things quickly. And it’s not just the technology that is changing, it’s things like the investment space. We’ve seen these divestment campaigns, there’s moves to say that unexploited hydrocarbon resource should be shown as a liability rather than an asset on a company’s balance sheet, for example.

And it’s those big policy changes that are sitting there in the background that I think will end up being a significant driver. When you’ve got a pension fund worth billions refusing to invest its money in a company because it hasn’t transitioned towards hydrogen or wind or solar, that ends up being a significant commercial pressure; that kind of policy finance space almost forces the technology. We’ve got a pretty good idea how to decarbonize society, but the other big challenge is energy storage, and that’s a big one. There’s 101 different ways to make energy out of the ocean, lots and lots of different ways of doing it. But how do you store that energy for demand peaks, or for days when the wind doesn’t blow or the sun don’t shine?

There is one other thing I should mention too. I first started working with marine autonomous systems back in about 1997-98, and they are becoming pretty advanced now, and they’re going to get more and more advanced as the years go by.

And we recently saw our friends in Russia deploy the first prototypes of something they call Poseidon, the NATO reporting name Kanyon, which is basically a nuclear powered and nuclear armed autonomous underwater vehicle for military purposes. Now, that’s fine, it’s Russia’s business if that’s what they want to deploy, it’s their sovereign right to do that. But in regards to marine law, these things evolved over hundreds of years going back to how far could you fire a cannonball. And as far as I can tell, if you try to look at what laws regulate of what you can do with an autonomous system, I think you’re looking at the 1907 Hague convention part eight which regulated rules pertaining to torpedoes and sea mines.

So here we are in the first quarter of the 21st century, and we’re still using a 1907 piece of legislation which was never intended to apply to a nuclear robot with a whopping grade thermonuclear nuclear warhead on the end of it. And I think both in the defense sector and also in things like autonomous shipping, we really need to start getting our grips not just on the technology, which is moving ahead at a fantastic pace, but make sure that our policy and legal frameworks are keeping pace with how the technology goes.

I can easily see a situation perhaps 10 years from now where you may have quite significant marine conflict going on with probably scarcity of human sailor anywhere involved.

- Obviously SUT has a lot of technology under its guise. Is there one that you see particularly literally important or instructive in pushing this industry forward faster in the coming years?

The general trend is taking humans off platforms, whether it’s taking them off oil and gas production systems or whether it’s taking them off ships. I think the movement towards putting human crew back into shore bases is going to be one of the most significant changes we see in the next few years. And it might be quite a surprise to our descendants 50, 60 years from now who realize, “Hey, do you know back in the 2020s people still actually worked on oil and gas platforms,” or, “they actually went out on fishing boats,” or, “they went out on ships?” Perhaps in some ways it’s a shame because I think there’s a great deal to be said for actually having people out there in that marine environment.

It’s easy to forget that we’re surrounded on all sides by ocean and that well over 90% of all of our trade arrives on a ship. When you get that shiny new pair of trainers from China, that didn’t fly in. A lot of our food is coming in that way, our energy is coming in that way. And I think this general kind of almost marine awareness is dropping out of the population in some ways. And if it’s happening in an island country like the UK, you can imagine even more so for folks who live in landlocked places far away. So I think it is a challenge for society as a whole to encourage people to understand that there is one planet, one ocean, that we’re all interconnected. And that ocean that used to divide us all is actually the thing now which unites us.

- When you use your career as bookends, what do you consider to be the one technology that has most made the business of working under water efficient?

I would say marine autonomous systems in recent years. That’s the thing which has certainly transformed the cost base. If you want to get data (from the ocean or under polar caps) relying on ships is doable, but expensive, with a big crew and a lot of technology behind you. Now, you can have almost disposable in the single use systems that can go out there in the midst of a wild storm, gather the data that your farmers and your planners need for better weather forecasting and all of those other things from these little yellow robots that are out there just constantly feeding data in and slowly beginning to make the ocean transparent.

There’s a long way to go, there are still massive gaps in our knowledge about the ocean. But the gaps are getting smaller. The robotics, the autonomy side has really changed things in my working life.

- One final question: we understand that your time with SUT is coming to an end; what’s next for Steve Hall?

I live in South Wales although I work in London and the other SUT centers. And to be honest, you don’t often get an opportunity to do really interesting marine science technology and policy job in my own home area, they don’t come up very often. So the opportunity came up with an organization called the Pembrokeshire Coastal Forum, which a number of projects, including Marine Energy Wales, which is looking after the introduction of floating offshore wind off the West coast. They’re also interested in sustainable coastal tourism. The vision of the organization is basically a sustainable coast and ocean. And the opportunity for new CEO came up with Pembrokeshire Coastal Forum and I thought, “Well, now this one sounds too good to give a miss too,” so I applied, and I got it. I’ll be starting at the end of December. I won’t disappear entirely from the SUT world, as I’m still a member and fellow of the society. So I’ll certainly carry on engagement with helping to grow the society internationally there and encouraging our links to MTS, IMarEST and others. I don’t disappear completely, but I’ll be focused much more on that kind of sustainability piece and the green issues, things like sustainable coastal tourism, sustainable marine energy, aquaculture, sea level rise, adapting coastal regions to a rapidly changing world. That will probably be how I see out the remainder of my full-time working life. And for the first time in, well, I think since 1987, I’ll actually have a job in the same country I live in. So I’m quite looking forward to that challenge as well.

We care about what our colleagues are doing, whether they’re out in the South China Sea or if they’re off the coast of Africa or in the middle of a North Sea storm ... everybody is facing those same hazards, the same beauty, the technical challenges. How do you anchor a wind farm in turbulent waters? Is it possible to extract manganese nodules or ferromanganese crusts from the deep sea bed without completely destroying the local ecosystem? We’re all aware of these challenges. And even after all of these years, there’s so little of the deep ocean floor that we’ve really explored.

We care about what our colleagues are doing, whether they’re out in the South China Sea or if they’re off the coast of Africa or in the middle of a North Sea storm ... everybody is facing those same hazards, the same beauty, the technical challenges. How do you anchor a wind farm in turbulent waters? Is it possible to extract manganese nodules or ferromanganese crusts from the deep sea bed without completely destroying the local ecosystem? We’re all aware of these challenges. And even after all of these years, there’s so little of the deep ocean floor that we’ve really explored.

December 2025

December 2025