Breathing New Life Into Fight to Save the Seas with Artificial Intelligence

It’s hard to imagine our planet without its oceans – their vast scale and depth, teeming with life. They’re also critical to tackling the climate crisis by storing vast quantities of carbon dioxide. But securing and expanding their stores of carbon depends on us being able to locate those stores and assess how healthy they are.

“Oceans cover 70% of the surface of the Earth, but we have so little understanding of them. It's really about getting that data and then, once we have it, we can make more impactful decisions,” suggests Christine Furthaller, head of growth at Montreal startup Whale Seeker.

This ranges from being able to gather and interpret data on the distribution of mangrove forests or seagrass meadows, to the contribution of whales to ocean carbon.

That’s where AI is proving a powerful tool – and specifically one branch called machine learning. Here algorithms are trained on big sets of data or images to quickly recognise the presence of a whale in a shipping lane, for example, or a fishing vessel in a marine protected area. The tools have become more powerful in recent years, with some of the biggest companies, like Google and IBM, using their software to map coastal blue carbon.

“It’s not really possible for a human to look at all of the data that's available and interpret it and draw out what really matters in any reasonable length of time, particularly given that fishing activities and other maritime activities happen everywhere all the time,” says Nick Wise, chief executive of OceanMind, a non-profit focused on enforcing regulations in our oceans. “Sifting through all of that and working out what is worth looking at is very much a job for a computer.”

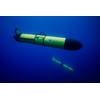

OceanMind’s AI systems have been trained to recognise a range of activities of different types of fishing vessels, to work out what a vessel is doing. Overlaid is a database of regulations and licenses. “The machine learning (system) essentially watches the vessels doing their fishing, works out where their fishing starts and stops and whether they should have been fishing in that location.” That information might be augmented by satellite data from NASA or the European Space Agency.

If anything looks amiss, for example a suspected transhipment of people or catch, it gets flagged up to one of OceanMind’s analysts, who can decide what to do next. That usually involves alerting a regulator, who can trigger a deeper investigation.

Some of OceanMind's projects are backed by NGOs, while others involve working with the seafood industry to ensure sustainable supply chains, or with governments. For example, OceanMind supports the UK government’s Blue Belt programme to monitor over 4 million square kilometres of ocean in its overseas territories.

Canada’s Whale Seeker, meanwhile, monitors marine mammals. It uses aerial and satellite image analysis tools to identify whales or polar bears, coastlines and ice. Going through images from a conservation organisation could take a biologist many months or even a year – and that’s certainly not scalable.

A key task is to help ships avoid whales, because ship strikes are one of the major causes of whale mortality. Whales play a critical role in ocean carbon sequestration in two ways: they themselves capture carbon, storing as much as 33 tonnes over their lifetime. Their diving and surfacing activities move nutrients through the water column and their excrement acts as a fertiliser for phytoplankton, which absorb carbon dioxide.

Furthaller describes whales as “ocean engineers”. Without them “that whole cycle would no longer be as efficient, with consequences for us.” That’s because phytoplankton play a significant role in taking up CO2 we have pumped into the atmosphere, and provide the oxygen for every second breath we take.

Its Whale Carbon Plus project, which brings together government and private sector, aims to put a value on the role of whales in carbon sequestration to incentivise organisations to protect them and help meet net zero goals.

Whale Seeker is a signatory to the 2017 Montreal Declaration for a Responsible Development of AI, which aims to put “AI development at the service of the well-being of all people”. To make good on that commitment, it aims to “develop solutions for good but also that are inclusive, so we really want to make sure that they can be used by, say, island nations that are on the forefront of climate change,” explains Furthaller.

That also means making its technology accessible, so that it not only works with military-grade drones or cameras, for example, but with more affordable off the shelf items; or has different pricing structures.

“First, and foremost, we meticulously vet the usage of our technology by our clients, to ensure our innovations are not exploited for harmful activities, such as whaling, which would be contrary to our mission of conservation and ethical use of AI,” Furthaller says.

They also validate their training datasets and verify the results through manual inspection, deliberately keeping the human in the loop. This also helps the model to improve. “It's really a combination of human expertise and the AI, to speed up the process considerably so that the decision-makers (in a company or government) can act on the data that they have in their hands.”

Whale Seeker also wants to help companies avoid greenwashing in their sustainability reporting, as they respond to pressure from investors. “Right now, it's very hard to get the data to do that reporting correctly, and not be accused of greenwashing. So that's another way we're hoping to contribute: to have solid data that you can audit and that you can verify, and that eventually could be used by companies to show their impact.”

AI might also help us address the scourge of the oceans: plastic pollution. As United Nations negotiators met in November to work on a global treaty, they were offered a new tool to help inform policy decisions. U.S. researchers at the Universities of California, Berkeley and Santa Barbara have used AI to develop an interactive model that allows them to simulate, in real time, the impacts of a policy – for example, on minimum recycled content or a packaging consumption tax – across multiple parameters, such as recycling collection rates and waste trade flows.

Crucially, negotiators can model the impact of multiple interventions to assess how they intersect with each other to reduce plastics waste while taking account of factors such as population growth and trade flows. Encouragingly, their modelled policy interventions show that plastics waste could be cut to zero. The researchers say they couldn’t have built the tool without AI. “The thing that we wanted to avoid was when there's a conversation between policymakers and they hit a question they don't have a good answer to and either they speculate, or they have to wait for weeks to do the analysis to figure out the answer.

Anything longer than a few seconds to resolve those questions just rapidly diminishes the impact of the work, so it was a crucial thing for us at the front of the project to say, how do we get this thing to run immediately – and deal with all the technical challenges related to that,” explains Sam Pottinger, senior research data scientist at Eric and Wendy Schmidt Center for Data Science and Environment at UC Berkeley.

Besides getting immediate results, Pottinger says that it was important to ensure that anyone using the tool could interrogate both the data and the code that manipulates the various policy levers. “It's essential from a scientific, and also a justice and equity standpoint, to be able to reason about these systems in depth.” He adds:

“It’s not enough for us to just to say, the model did it and not ask any more questions.”

While AI technologies are becoming more powerful and versatile, they need to scale to have real impact. “I don't think we need more technology,” suggests Wise. “The vast majority of technology use is really on a pilot scale today. Even the work that we're doing is fairly local, (at) individual nation level. But our technology, and many others like it, are globally scalable. So we need funding, and we need engagement. And that's the hard part: to choose to use the technologies that are available and take action.”

And it comes down to humans to make those decisions.

(Reuters - Opinions expressed are those of the author. They do not reflect the views of Reuters News, which, under the Trust Principles, is committed to integrity, independence, and freedom from bias. Ethical Corporation Magazine, a part of Reuters Professional, is owned by Thomson Reuters and operates independently of Reuters News.)

February 2025

February 2025