SOI Steps Ahead on Ocean Mapping

With its new research vessel Falkor (too), Schmidt Ocean Institute (SOI) has ramped up its ability to map the ocean floor. Jyotika I. Virmani, Ph.D. Executive Director, SOI, offers insights on how new and emerging meld with onboard and shoreside crew to make exploration and discovery more efficient and effective.

Jyotika, to start, can you give us a ‘By the Numbers’ look at SOI today?

We recently donated our original vessel, Falkor, to Italy in 2022. In the last 10 years of operating Falkor when we had 81 expeditions, with over 1,800 days of science at sea. And we hosted over a thousand scientists and 340 or so students. In addition to the science, we also have an artist at sea program. On Falkor we also hosted over 40 artists and so we have a portfolio of art that we also exhibit in addition to the science. Falkor was really a wonderful vessel and has now gone on to a new career. But with that we mapped about 1.3 million square kilometers of sea floor and found numerous underwater features. FALKOR (too) underwent refit in a Spanish shipyard for 17 months; a much bigger ship than Falkor with loads of new room, labs, and potential to expand. Photos courtesy SOI

FALKOR (too) underwent refit in a Spanish shipyard for 17 months; a much bigger ship than Falkor with loads of new room, labs, and potential to expand. Photos courtesy SOI

It wasn't long ago that SOI added its new ship, the Falkor (too), to its arsenal of ocean research capability. Talk, if you will, about this strategic asset. What new capabilities did it add or expand and what missions specifically has it been on since joining the fleet?

Falkor (too), our new research vessel, is a 110 meter global ocean class vessel, it's much bigger than Falkor. It has an aft deck with over 900 square meters which allows us to plug and play different types of labs in containers. We can morph this vessel to meet any science need that may arise. As permanent parts of the vessel, we have a 150-ton crane, and we're going to work out how that can be best utilized. We have two moon pools, one internal and one on the aft deck. The largest one is over seven meters by seven meters and the smaller is five by five. We have multiple launch and recovery systems, so that allows us to put many different instruments in the water at the same time. It also has incredible dynamic positioning capabilities and great maneuverability [courtesy of its Voith Schneider Propellers].

The vessel was refit in a shipyard in Spain for about 17 months, because when we got the vessel there were no science capabilities on board, so we have added eight labs.

There's the main lab which is 105 square meters, as well as a wet lab, dirty lab, cold lab, seawater lab, computer and electronics lab, plus a robotics lab. And we added a mission control room.

We kept our ROV SuBastian from Falkor and that's our ROV that can go down to 4,500 meters. We also have over a hundred different science sensors and science equipment for ocean and atmosphere capabilities.

I'd like to dig a bit deeper into this asset’s mapping capabilities: specifically, can you speak to Falkor (too)'s sub-sea mapping capabilities and potential?

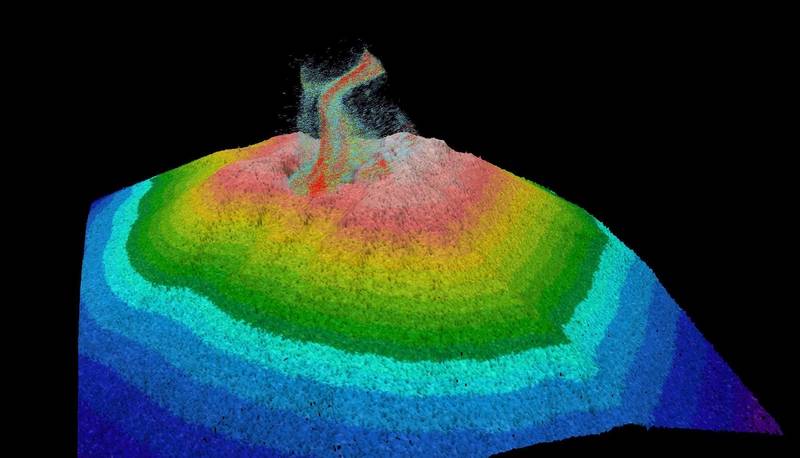

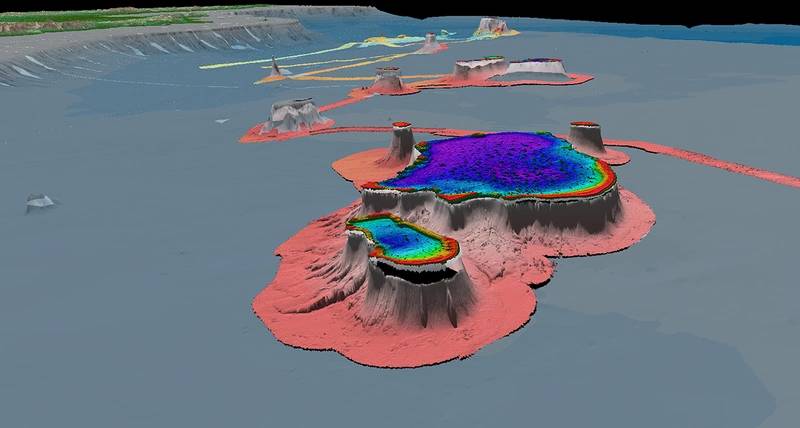

Part of what we added during the refit was a 19-meter gondola under the hull. Within that gondola come a number of different sonar capabilities. We've got Kongsberg EM 2040, EM 712, and an EM 124. That really gives us the ability to do complete ocean depth sea floor mapping down to 11,000 meters at very high resolution.

We also have some mid-water echosounder, EK 80. We've got a couple of echosounders and then we also have sonars of course for fisheries and navigation purposes as well as current meter capabilities. Then we also have a Kongsberg SBP 29 sub-bottom profiler. We have a lot of acoustics on board the vessel, but really for the mapping we have a pretty impressive suite of sonar capability. [This ship also] expands our capabilities. It’s ice-rated as well so it can go through about 10 to 15 centimeters of ice, meaning it can go into summer ice or first ice, allowing us to now go to higher latitudes.

“I think we're looking at a future of increasing our robotic capability on board as well as our machine learning and processing of that data as well.”

“I think we're looking at a future of increasing our robotic capability on board as well as our machine learning and processing of that data as well.”

Jyotika I. Virmani, Ph.D. Executive Director, SOI

Image courtesy SOIWhen you look at the evolution of seabed mapping capabilities using your career as bookends, is there one or two technologies or what technologies do you see as having the greatest impact on making the process more efficient?

Autonomous mapping [with autonomous and remote controlled surface and subsea vehicles] is a huge leap forward. That capability is huge because you can now deploy multiple of those and not only map from the surface, but also with AUV simultaneously. And being able to control all of that and change the course and track from the coastline is a huge leap forward. And then adjacent to that we are seeing improvements in communications and how we can get data from far reaches of the ocean back to land. We now have Starlink [on Falkor (too)] as well as other satellite means so we now have capability for improved communications and greater bandwidth and return of data.

The ability to collect more and better data is one thing. The ability to process these fast, new quantities of data is quite another. Do you see any technologies or techniques today that are evolving today that will enable efficiencies in turning these mountains of raw data into actionable intelligence?

Yes I do. There is some in the bathymetric range, but I think the biggest advances I'm seeing are in biological oceanography and the ability to handle and process that data. What we are using, for example, we have this ROV that has amazing video capabilities and we've got hundreds of hours of video footage, not just of creatures, but also the sea floor. But it takes a lot to process that and to identify every single feature and every single creature. That's where some of these techniques are really kicking in, for example, MBARI's Ocean Vision AI program. The end goal is to have machines and machine learning code help process all of this video footage [using artificial intelligence, too] to help speed up our ability to process that data, especially the more routine tasks that we currently are doing with humans.

Can you discuss, SOI's mapping work under Seabed 2030 and how it fits into your overall organization plan?

SOI has been a partner with Seabed 2030 since 2019, and all the mapping data that we collect goes into the Seabed 2030 general bathymetric chart of the ocean's database. The data that we collect feeds into that. As I mentioned earlier, we've had over 1.3 million square kilometers and we continue to map with Falkor (too) and all of that will continue to feed into Seabed 2030 as well. But as a partner, we also have a focus, and our strategic framework includes that mapping and our strength is really deep sea and high seas, so some of the more difficult to reach places. We can get to places that we currently have big gaps in the sea floor map of and try and make a bit more of a concerted effort to map those areas for the Seabed 2030 program. THE BLACK SMOKERS were teeming with life.

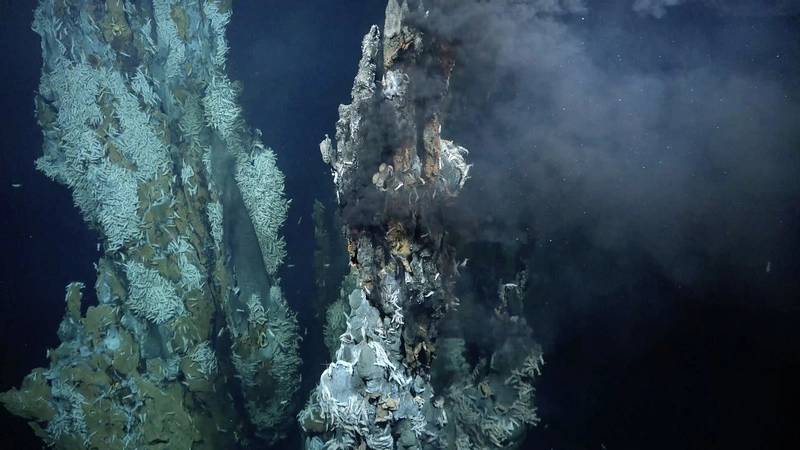

THE BLACK SMOKERS were teeming with life.

Photos courtesy SOI

From where you sit, how does seabed mapping fit into this whole ocean health conversation?

I've said this for many years, but I think a map is a fundamental piece of understanding our planet. Without that basic understanding, you can't really value something and without putting a value on something, you really don't care about the health of something.

To give you a couple of examples, our first cruise on Falkor (too) was to the Mid-Atlantic Ridge looking for hydrothermal vents. They found three new hydrothermal vent fields, countless black smokers teaming with life.

This area had been marked for sea floor mining because there was an understanding that there was no real life down there, but if you look at the shrimp party we found via ROV SuBastian's video footage, there is a lot of life down there. We mapped using Falkor (too)'s ship capabilities, and we had MBARI's AUVs with us on board, sent down to do a very high-resolution map of areas of interest.

And then we had a CTD that went down and measured the chemical composition. Then we sent the ROV down, and almost every time they found something new.

Our second cruise was to test technology, as we also have technology test cruises and not just science and exploration. That one was to test new sensors for coral reef health assessment around Puerto Rico. First, they found much more biodiversity than had previously been suspected around Puerto Rico. But the idea was to look at reactive oxygen. It is a new sensor that they were testing called SOLARIS. The prototype for that was an instrument called DISCO, similar, but for much shallower water, which was funded by Marine Technology Partners. As I mentioned, it found greater biodiversity, and they're still working on the data, but new coral species as well.

The third cruise was our Octopus Odyssey off Costa Rica. That was to go and look at an octopus nursery that had been discovered in 2013. Back then, there was no evidence that the octopus that they'd seen had viable eggs, no real evidence of this being a nursery. When we went out this year, we saw hatchlings and little octopus. It actually was a viable nursery, which was huge. And not only that, they then found another octopus nursery, a second one in a different part of Costa Rica.

Now I think in total there are four octopus nurseries in the world that have been discovered. But it ties into everything that you've been talking about from the mapping, knowing where the sea mounts are, so where the diversity is to investigate, but then leading to ocean health. I mean, if this area had been destroyed, you'd destroy an entire species of octopus because it's their nursery. You would destroy an entire generation right there in one go.

Can you discuss how SOI is investing in technology and capability in the coming few years to ensure that its strategic plan, its mission, will be carried out?

Our strategic framework has seven topical areas that we're focusing on, of which mapping is one. Within those, there are sub-regions that we have identified, but biodiversity, the frontiers of biodiversity is another area that we're really keen on assisting and helping with. We're a partner with Ocean Census, which is a relatively new program to find a hundred thousand new marine species in the next 10 years.

The technologies that we would be really looking at investing in, supporting, we want to build out, of course, our biological capabilities on board. But this is a new ship for us. This is the first year of our shakedown cruises. We're still testing everything and learning the vessel itself. But in the next few years, I think we will start to add some of the remote and autonomous technologies that we just discussed.

So for example, a Saildrone or a SEA-KIT, something like that, an autonomous surface vessel, potentially an AUV. With that when th scientists get out there, they know what they're looking for and where they're looking, whether it's a sea mount which has enormous biodiversity or hydrothermal vents. Then we can use the vessel [even more] effectively for the scientists to do their research, which is a little more complex at this stage than the mapping. I think we're looking at a future of increasing our robotic capability on board as well as our machine learning and processing of that data as well.

Watch the full video interview with Schmidt Ocean Institute’s (SOI) Executive Director Jyotika I. Virmani on Marine Technology TV:

![Microplastic beads seen in the central tube of a copepod [their intestinal tract], as evidenced here, fluorescently labelled beads help with visualization and identification. © PML](https://images.marinetechnologynews.com/images/maritime/w100h100padcanvas/microplastic-beads-seen-166795.jpeg)

December 2025

December 2025