Searching for Shipwrecks

The ice had barely retreated from the coast of northern Lake Huron this spring when a group of farflung researchers converged in Rogers City, Michigan. They were there to map unexplored areas of Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary. If all went well, they would discover new shipwrecks and natural features such as sinkholes, fish habitats, and interesting geological formations.

During the two-week expedition, researchers mapped areas within the sanctuary with a multibeam sonar system aboard autonomous surface vehicle ASV BEN (Bathymetric Explorer and Navigator) from University of New Hampshire’s Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping. BEN is a state-of-the-art robotic vehicle that looks like a small yellow boat. Unlike most boats, though, it doesn’t carry people; instead, it is piloted by crew members back on shore. Using sonar and GPS, BEN collects data about the lake bottom that can be used to create high-resolution maps. The expedition in Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary also served as a test case, helping engineers improve BEN for future uses.

Researchers aboard the R/V Storm, operated by NOAA Great Lakes Environmental Research Lab, supported BEN and also conducted mapping and surveying in adjacent areas of the lake. Sponsored by NOAA’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries, this project marks the first partnership between Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary and Ocean Exploration Trust.

"Working with Ocean Exploration Trust is an incredible opportunity for the public to discover Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary,” explains Jeff Gray, sanctuary superintendent. “Not only does Ocean Exploration Trust bring scientists from around the world to conduct cutting-edge research in northeast Michigan, but through innovative education and outreach programs, these scientists share the sanctuary's incredible underwater treasures with the world.”

NOAA’s R/V Storm waits for ASV BEN to leave the Rogers City marina to start mapping operations in Lake Huron during the expedition. (Photo: David Cummins/Alpena Community College)

NOAA’s R/V Storm waits for ASV BEN to leave the Rogers City marina to start mapping operations in Lake Huron during the expedition. (Photo: David Cummins/Alpena Community College)

Why explore Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary?

Located in Lake Huron, NOAA’s Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary was established in 2000 to protect one of the nation’s most historically significant collections of shipwrecks. In 2014, the sanctuary expanded from 448 to 4,300 square miles, making it the nation’s largest marine protected area focused on underwater cultural heritage sites. Within this new boundary are 99 known shipwreck sites, while historical research indicates as many 100 additional sites in the area remain undiscovered.

The shipwrecks of Thunder Bay represent a nearly complete collection of Great Lakes vessel types, from small schooners and pioneer steamboats of the 1830s to massive industrial bulk carriers that supported America’s heavy industries during the 20th century.

This expedition is helping to provide baseline information that will help the sanctuary better understand and protect these underwater cultural heritage sites. In addition, the data researchers collect can be used to produce lake floor habitat maps of coastal Lake Huron’s ecosystems.

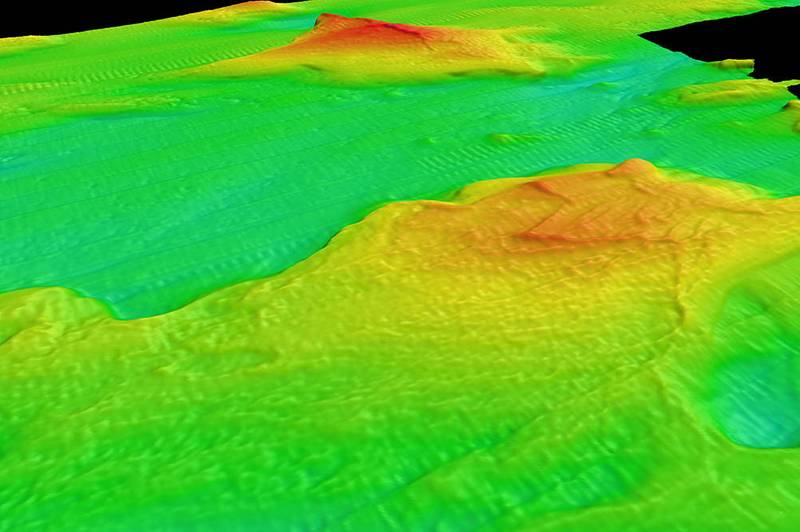

A processed bathymetry map shows the Lake Huron bottomlands in Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary using data collected by ASV BEN. Varying colors indicate different heights of interesting lakebed features (heights are exaggerated to make the features clearer). This type of map may be used to characterize lakebed and habitats, as well as plan future exploration. (Image: OET/UNH-CCOM)

A processed bathymetry map shows the Lake Huron bottomlands in Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary using data collected by ASV BEN. Varying colors indicate different heights of interesting lakebed features (heights are exaggerated to make the features clearer). This type of map may be used to characterize lakebed and habitats, as well as plan future exploration. (Image: OET/UNH-CCOM)

Venturing into Shipwreck Alley

The targeted survey area in northern Lake Huron embodies the diverse and rich maritime cultural landscape of the Great Lakes, including dangerous, near-shore shallow waters and the deep, mid-lake waters of busy shipping lanes. Dubbed “Shipwreck Alley,” the shipping lanes in northern Lake Huron are notorious for heavy vessel traffic and intense weather patterns that have sunk many ships.

Given the high-tech, experimental nature of ASV BEN, the team assessed and prioritized these areas of interest in real-time during the project, adjusting which areas they were targeting as needed depending on weather and other factors. In addition to searching for shipwrecks, the expedition gave researchers and engineers the opportunity to test BEN’s telemetry range and refine its performance capabilities for future expeditions.

Surveying in these waters can be challenging, but it can also be fruitful. In 2017, Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary, University of Delaware, and Michigan Technological University discovered and identified the wooden freighter Ohio, which suffered a fatal collision with the schooner Ironton in 1894. Ironton, which also sank after the collision, has yet to be found, and scientists were on the lookout during the expedition.

In addition to the potential discovery of historically-significant shipwrecks, sanctuary waters in Lake Huron also hold the potential for unique natural features such as sinkholes with links to ancient ecosystems, glacial features of interest, and important fish habitat. “Five years ago the marine sanctuary’s boundaries were expanded to 4,300 square miles and only 20 percent of the lake bottom has been surveyed in this area,” explains Stephanie Gandulla, sanctuary research coordinator. “So this multi-year mapping effort is incredibly valuable for us.” This year’s expedition successfully documented many of these features with the bathymetric data gathered, and the team looks forward to expanding the survey area in 2020.

This is a processed bathymetry map of the lakebed in Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary using data collected by R/V Storm. Varying colors indicate different heights of interesting lakebed features (heights are exaggerated to make the features easier to see.) This is a zoomed-in, higher-resolution version of the similar ASV BEN map above. (Image: OET/NOAA)

This is a processed bathymetry map of the lakebed in Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary using data collected by R/V Storm. Varying colors indicate different heights of interesting lakebed features (heights are exaggerated to make the features easier to see.) This is a zoomed-in, higher-resolution version of the similar ASV BEN map above. (Image: OET/NOAA)

The Author

Sarah Waters is the education and outreach coordinator for Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary.

This article is republished with permission from Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary.

December 2025

December 2025